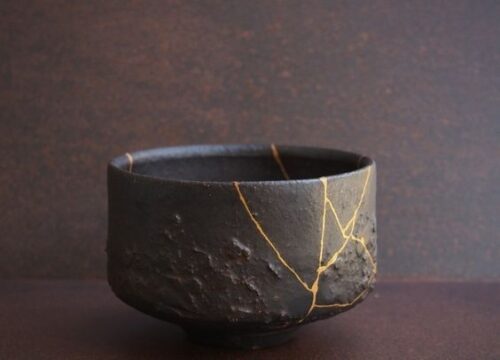

Japanese teacups differ significantly from their European counterparts, often featuring handmade characteristics that include intentional roughness and intricate patterns. Many of these cups may even show evidence of past damage, artfully mended with gold through a technique known as Kintsugi.

The origins of Kintsugi date back to the 15th century when Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent broken teacups to China for repairs. Upon receiving them back with unsightly iron seams, he sought a more aesthetically pleasing solution. Japanese craftsmen ingeniously combined shellac with gold to transform the cracks into beautiful, artistic features. This technique quickly gained popularity, with some collectors even intentionally breaking valuable pottery to repair it in this fashion. Kintsugi embodies the philosophy that broken items should not be discarded but rather restored, much like our lives, which are often marked by pain and loss. The act of mending symbolizes resilience, allowing us to regain strength, happiness, and a deeper understanding of ourselves and others.

At its core, Japanese philosophy embraces the notion that no life is without flaws. Kintsugi invites us to acknowledge our own vulnerabilities and to cultivate inner strength. By treating broken cups with care and affection, we learn to accept and respect the imperfections in ourselves and those around us, ultimately leading us to genuine happiness.

While a Kintsugi teacup can still serve its purpose, it remains imperfect—reflecting the idea that there is beauty in simplicity and that we need not strive for a flawless replacement. This philosophy is deeply ingrained in Japanese culture, advocating for humility and appreciation of the natural aging process. This concept is known as “Wabi-sabi,” which celebrates the beauty of imperfection and the transient nature of life.

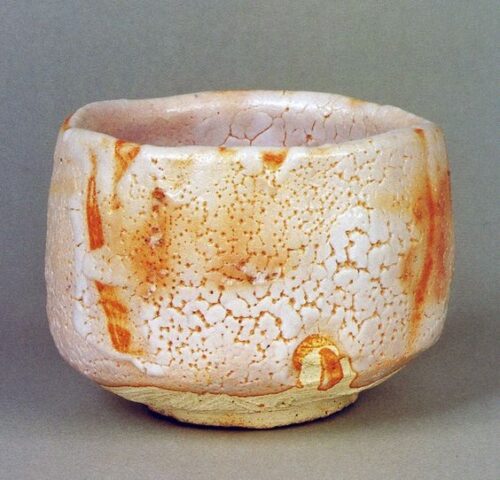

“Wabi-sabi” has influenced various design styles, including Loft, Industrial, Rustic, and Minimalist aesthetics, as evidenced by the teacups commonly used in Japan. These vessels often feature unrefined edges, creating a tactile experience that contrasts with the polished surfaces of conventional teacups. Rather than aiming for opulence, these cups invite the tea drinker to engage in a state of calm and simplicity, embodying the essence of “Wabi-sabi.”

The art of the teacup emerged alongside the rise of the Japanese tea ceremony, which was significantly influenced by Zen Buddhism. This practice became a cultural phenomenon among the elite, including samurai and affluent merchants. Tea utensils, often imported and adorned with extravagant decorations, became symbols of status. For example, during 1585-1586, Hideyoshi commissioned a gold-covered tea room for Emperor Ogimachi, yet he chose to serve tea in a simple teacup. This gesture encouraged guests to appreciate the unembellished beauty of the moment, emphasizing that true beauty transcends external appearances.

Wabi-sabi principles are also reflected in the architecture and craftsmanship of traditional Japanese tea houses. Typically distinct from other buildings, these tea houses are intentionally small, constructed with natural materials that are designed to age gracefully. In contrast to Western architectural ideals of permanence and perfection, Japanese structures, such as wooden houses and paper doors, embrace the inevitability of decay.

Inside the tea house, the design accommodates no more than five guests at a time, with an entrance door just 80 centimeters high. This requirement for guests to crawl through fosters a sense of humility and equality, encouraging a shared experience devoid of ego.

Within the tea room, cups, bowls, and utensils are crafted from natural materials, each bearing marks and stains that tell the story of their use over time. This embrace of imperfection promotes a broader perspective on beauty, illustrating that life does not need to conform to an ideal of perfection. Through the lens of Wabi-sabi, we find meaning and aesthetic richness in the ordinary, the flawed, and the ephemeral.